Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū | Curated by Chloe Cull, with contributions from Dr Kirsty Dunn and Dr Madi Williams (Taniwha: A Cultural History Project)

Taniwha are not allegories. They are not safely symbolic, nor reducible to decorative figures from a mythic archive. Whāia te Taniwha makes this abundantly clear.

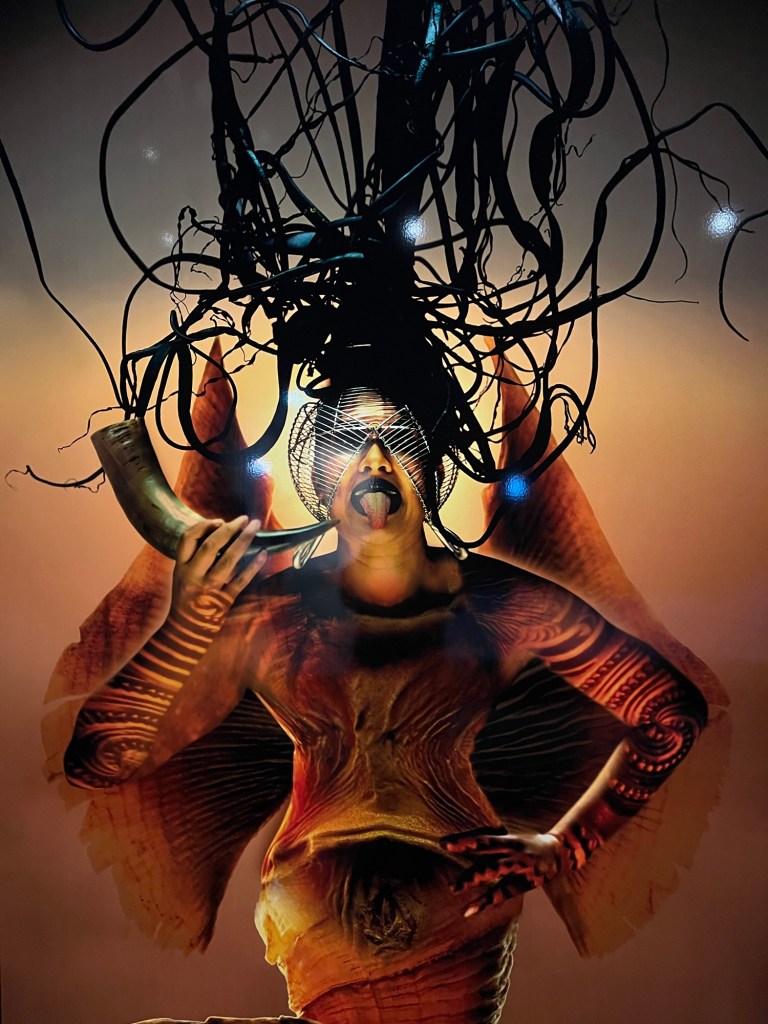

This major exhibition resists the colonial impulse to pin taniwha down into singular categories — monster, demon, or even protective spirit. Instead, it insists on taniwha as relational beings: oceanic guides, shape-shifting ancestors, adversaries, guardians, tricksters, ecological presences. They are as unstable as they are vital. This refusal of fixed definition is where their power lies.

Curatorial Gesture: Defiance as Method

Curated by Chloe Cull (Pouarataki curator Māori), and emerging from the wider research of Dr Kirsty Dunn and Dr Madi Williams’ Taniwha: A Cultural History Project, the exhibition performs a radical inversion: rather than translating taniwha into categories legible to Western art discourse, it demands that audiences dwell with uncertainty, opacity, and multiplicity.

This is a decolonial curatorial act. It unsettles the Enlightenment desire for clarity, taxonomy, mastery. Instead, Cull and the artists affirm the taniwha’s capacity to slip between forms, evade capture, and haunt the colonial landscape with ancestral, ecological, and political force.

The Works: Hybrid Tactics, Living Relations

From Lisa Reihana’s cinematic poetics to Maungarongo Te Kawa’s textile interventions, from interactive AR sculpture to a video game where taniwha are not enemies to be conquered but beings to encounter, the exhibition proliferates mediums. This heterogeneity itself enacts taniwha logic: resisting containment, refusing singular form.

Local Ngāi Tahu artists like Jennifer Rendall, Fran Spencer, and Kommi Tamati-Elliffe ground the show in whakapapa and whenua, situating taniwha as inseparable from Aotearoa’s landscapes and waterscapes scarred by colonial modernity.

Taniwha as Counter-Modernity

If modernity has been a project of flattening — disciplining land, water, people into extractive grids — taniwha erupt as counter-modern figures. They remind us of rivers that cannot be fully dammed, of knowledge that cannot be domesticated, of ancestors who refuse erasure.

In this sense, Whāia te Taniwha is not simply an exhibition about “mythical creatures.” It is an insurgent archive of survivance. It asks: what does it mean to live in a world still populated by beings that modernity denied?

Rupture

The exhibition ruptures both art historical and political narratives. For non-Māori audiences, it is an unsettling encounter with a worldview in which human exceptionalism dissolves. For Māori, it can be a space of recognition, resurgence, and affirmation — though always without simplification.

Taniwha are never safe. They are guides and threats, protectors and challengers. In a time of ecological collapse and cultural erasure, they remind us that relation is not comfort, but responsibility.

Final Note

Whāia te Taniwha demands we attend to taniwha not as folklore but as living presences that continue to shape whenua, water, and collective futures. The exhibition is itself a taniwha: shape-shifting, elusive, powerful, unsettling — and urgently necessary.

Leave a comment